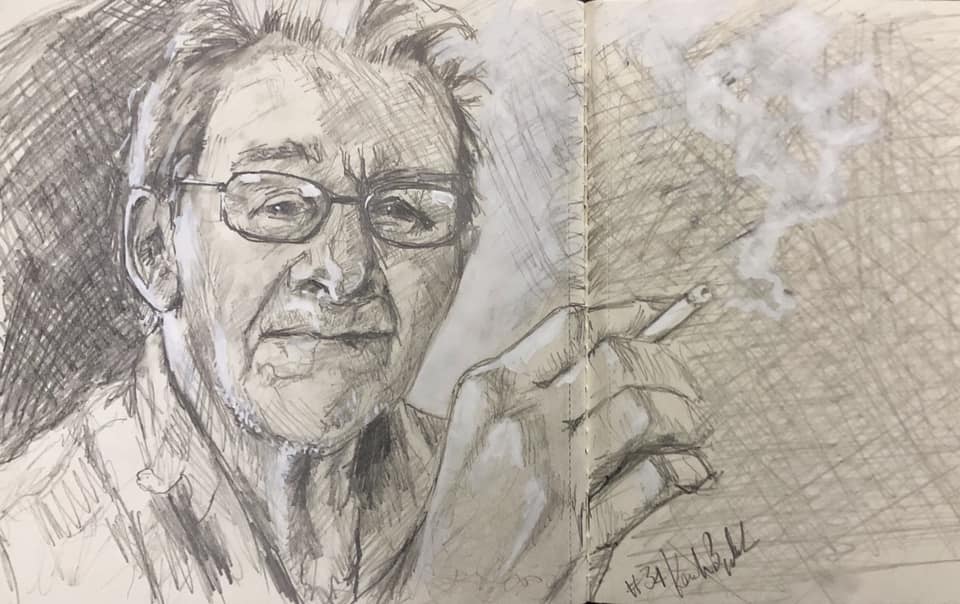

Peter Van Toorn is the author of three books of poetry, Leeway Grass, (1970); In Guildenstern County, 1973; and Mountain Tea, 1985. As editor, he has published various collections over the years: Cross/cut: Contemporary English Quebec Poetry (with Ken Norris), 1982; The Insecurity of Art: Essays on Poetics (with Ken Norris), 1982; Lakeshore Poets, 1982; Sounds New, 1990; and most recently, Canadian Animal Poetry, (1993).

Born July 13th, 1944 in a bunker near The Hague, Netherlands, Van Toorn has lived in and around Montreal since 1953. A former student of Louis Dudek, F.R Scott, and Hugh Maclennan, he worked for a while as a teacher’s assistant to Hugh MacLennan at McGill University grading papers. During the late 60s and early 70s, he taught at Concordia University. Now, after 29 years of teaching Creative Writing and Canadian Poetry at John Abbott College in Ste. Anne de Bellevue, he is retired. He lives in a small semi-detached rented house with three dogs, seven cats and his girlfriend of 11 years, Annie.

I’ve always admired his translations in Mountain Tea, so when I reached Peter by phone Monday evening, October the 24th, 2000, I asked him to talk a little about translation.

Phone interview

NW: What is translation?

PVT: The word itself is interesting: it comes to us from translatus,the past participle of the Latin transferre, ‘to carry across’ without death. Right there you have the mandate of the poetic translator like me. There’s no point translating something, unless it lives in the language into which it goes. If doesn’t live in the new language, it’s like a transplant—it gets rejected. It’s not successful.

NW: Peter, where did translation start?

PVT: It was Babel, a plain in the land of Shinar, tradition tells us, where they first discovered a need for it.

A long time ago, the men who lived there said, “Let us build a city and a tower that it may reach unto heaven. And let us make us a name lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language. Nothing will be restrained from them which they have imagined to do. Let us go down and confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.”

And the people of Shinar said, “Let us use slime for mortar and brick for stone.” In other words, they were going to have to extemporize, and adlib, and use materials that were handy—they were being ingenious and creative, right? And they thought this was clever. But they had given up trying to reach God through prayer and meditation.

What they wanted was technological power. They wanted a real, physical power to reach God, as if he’s really up there. That, in itself, is problematic. They had become literalists of the imagination.

So God smashed the tower and scattered the bricks, and suddenly people couldn’t understand each other. They’d lost their ability to collaborate and got scattered across the earth. That’s where the need for translation started.

NW: So translation has been valued ever since, right?

PVT: In fact, no. The opposite is true. There’s been a taboo on translation that has beleaguered translators since Babel. To this day, Jewish scholars are not allowed to translate. They are not even allowed to touch a text until they’ve washed their hands and performed certain rituals and said certain prayers. They’re very, very afraid of what they call an irreption, which is a kind of corruption where a little deviation crawls into the text through a smudge or a tired moment of the copyist.

Translators to this day have been beleaguered by this taboo. And you see that every time you pick up a book that has been translated. The translator always has a heavy apology in the front saying, “In my translation, I have sought to preserve the alliteration of the Norse text without imposing too high of a diction…” and they go into a whole elaborate explanation of how they’ve translated the damn thing, which nobody really wants to hear. We just want to see a poem that works! If it doesn’t work in the new language, if it isn’t a poem in its own right, then it’s not a good translation, so there’s no point in doing it.

I’ll give you a little illustration of the whole problem of translation.

During the 1940s there were musicians living in Czechoslovakia during the Communist era who really prized and loved to play jazz. They just loved it. To them, jazz was the symbol of the freedom of America, of everything that was tantalizing. So they would send away for sheet music to New York City and get standard jazz pieces, which they would then play. One piece they got in the mail, one day, was called, “Stomping at the Barbecue.” And this is how they translated it: “Dancing Slowly at an Outdoor Cooking Device.”

You can see how clumsy that is. It doesn’t live in the new language.

It’s a literal translation, but it isn’t interesting, it isn’t funky. It doesn’t live in Czech.

The whole thing then is for the Czech translator to find what Elliot calls the objective correlative, something in Czech culture that is familiar to them like the barbecue, their word, their thing for it. And if there’s no barbecue, then to find another object, to make “Stomping at the Barbecue” live in Czech. Otherwise, they’re not extending the national, linguistic, temperamental, and chronological boundaries of the source text.

NW: What do you mean by temperamental boundaries?

PVT: A translation has to carry a poem across boundaries of geography, language, and time, as well as temperament. The temperament of the translator may be very different from that of the poet of the source text. Only at certain moments will the translator be congenial enough to the source poet to accommodate that certain point of view that he, himself, would maybe never write about. Then translation becomes the one permissible way for the translator to write about something that’s very personal.

NW: Forgive me for asking this: Isn’t translation just another form of cultural imperialism, you know, going around the globe swiping masterpieces and pocketing the proceeds?

PVT: It can be. It’s not supposed to be. I know what you mean, though. Translation requires reciprocity. You have to give something back to the original.

A translation should always carry the poem further, into the next time, into the next Zeitgeist, into the next cultural mood. If Beaudelaire were writing that poem now, if he were writing in English and he wanted to translate the poem himself, this is what he would have done. You have to ask yourself: what if he were translating his poem into English and not me. That’s what you aim at, so the poem extends its readership.

A good translation can give the source text an immensely wider circulation than it originally had when it was just confined to the French readers of that century. Another country or another time may be more receptive to a Beaudelaire poem than even the Parisians were at the time it was first written.

NW: How did you get started doing translations? What was your first translation?

PVT: First translation? Good question. Gee, that’s a toughie. Okay, yeah—Latin. In high school, I don’t know about you, but I took Latin. That was my first real experience as a translator. In high school, all kids had to translate Caesar and Tacitus and all the groovy guys like Ovid into English. So you learned another language mechanically.

I think the first thing I translated successfully is my poem in Leeway Grass, the one about the sword maker, “Elegy on War: Invention of the Sword,” from Tibullus. From there I went on to French, because you learn French at school if you grow up here. I translated Beaudelaire, Villon, Ronsard, Charles d’Orleans, Rimbaud, Manger, Hugo, Saint-Amant…

NW: Any Quebeckers?

PVT: Sure. Gilles Vigneault and Sylvain Garneau.

NW: What about your translations from languages you don’t speak?

PVT: Here we get into another thing. [Coughs] I see that problem as being a problem of research. When you do anything in research, you don’t just read one book. You come at it from a hundred directions. You look at a hundred different texts by scholars who are very knowledgeable in the original tongue. Let’s say Chinese in this case. So you read the famous scholars who have translated it, and you read other people who have tried it. Because they’re not fully translated in the sense we talked about earlier and since they are still kind of klutzy and eminently forgettable, that stuff gets to be dust in the next century.

But if you look at all these different texts, they all seem to be pointing at something. You can find that point by triangulation. When you know points around something you can find where the center is. So I would go to different Chinese translators and found their translations not sparkling enough, but I could sort of smell the original. Goethe said, “Translations are like pictures on matchboxes; they make you hungry for the original.”

Often, translators demote poetry to prose in their translations. Robert Frost said something very witty about translation once. His definition of poetry went like this: “Poetry is what gets lost in the translation.” [Laughs] So a poetic translation is as Elliot says, a raid on the inarticulate. Il faut etre poet, d’abord! Translation means taking that poem one step further, back into poetry where it belongs. ‘Cuz if it ain’t got that swing, it don’t mean a thing…[Chuckles]…

NW: Thanks, Pete.

PVT: Anytime.

Related posts

- Grammar checker poem

- Translation card game

- Translate your grammar checker feedback to one of 70 languages

How I met Peter Van Toorn

Peter Van Toorn and I first became friends in 1987. Our friendship started with an argument over a word. Halfway through the semester at John Abbott College, Professor Van Toorn gave our Creative Writing class an assignment that started an argument that has never been settled.

The assignment was “to find ten uses of the word ‘spit’ and put them into ten sentences, each illustrating one of the meanings of the word.” The rest of the class groaned when he announced the assignment because it meant a trip to the library and laborious use of dictionaries. I was intrigued. I took it as a challenge and went directly after class to the library determined to find a use of “spit” that he was unlikely to encounter in the papers from the groaning population of the class.

There in the college library, I found several giant dictionaries and went through them looking for the one with the most entries under the heading “spit.” I can’t remember the name of the dictionary I found, but it was so large that a librarian came over to help me lift it.

It had 18 entries—more than enough to complete the assignment. Of course, there were the common uses that most people know: spit meaning to eject phlegm, spit meaning sputum, spit meaning a rotisserie rod, and the idiomatic usage, “spit and image” mistakenly pronounced “spitting image.”

Also listed were the ones people usually don’t know: spit meaning to run through, spit meaning a short sword, spit meaning a sandy promontory, and spit meaning the quantity of earth taken up by a spade at a time. But it was the final entry that really intrigued me: spit-kit meaning a tin box used by military personnel to hold tobacco and rolling papers with a compartment to extinguish lit cigarettes and store the butts.

Upon reading this, I was reminded of my grandfather back in England who kept his tobacco, papers, and “fag-ends” in a tin he kept in his breast pocket.

“Professor Van Toorn is going to love this one,” I thought. “I bet even he hasn’t discovered this usage!”

I completed my assignment putting “spit-kit” first in my list with the sentence, “The soldier extinguished his cigarette in his spit-kit,” and gave it in the following week. When I got my assignment back a week later, I was horrified that Peter had given me 9/10 with an “X” next to my first sentence and the word “argot” in the margin. I had no idea what “argot” meant, but I was quite sure of my research and that he had just never encountered “spit-kit” before.

I was right. He hadn’t seen that usage before but explained that “spit-kit” was a usage of “spit” not belonging to the general current of English and was therefore unacceptable, as would be slang, jargon, or other highly specialized uses of the word. Well, that got me miffed. I felt he had unjustly penalized my work for going further in my research than anyone else in the class including himself, the professor.

Sensing my indignation, he suggested we settle our quarrel over a beer at the brasserie in the village. Peter is a good talker. I learned more in the four hours we spent drinking together than I had learned all semester in any of my other courses. I could not, however, get him to agree to change my grade. He said, “If I haven’t heard of it, it doesn’t exist. You must have made it up.”

Something changed inside me.

I couldn’t believe how arrogant that was. Peter, by his intractability, had awoken in me the strength to dare to disagree with my professors, to trust my own research, to go further in my reading than them, and, above all, to distrust orthodoxy of any kind in the realm of ideas.

Years later, he related to me how his professor at McGill University, Louis Dudek, had taught him never to trust any scholar as having the final word on a subject. “Scholarship,” Peter said, “means maintenance. Trust no one, not even yourself. Everybody gets things wrong sometimes. Read and reread and never stop. Keep going back to your research time and again until it becomes impossible to forget.”

“Spit-kit,” I said.

“Grade change,” he replied.

Some people have a professional interest in poetry; they are professors of literature, students, book reviewers and such. Peter Van Toorn is different. For him, poetry is fundamental to what he calls a life worth living. If Peter has a religion of any kind, it must be in poetry. He once described poetry as having transformed him over the years, “molecule by molecule until there is nothing left of the original.” He says, “Most people don’t know what they want—but they want it anyway. Poetry allows me to ask for it by name.” Peter knows what he wants and gets it.

He lives in a small semi-detached house with 3 dogs and 7 cats and a whole lot of clutter. The walls drip with years of accumulated grime. There’s a hole in the screen door to the kitchen with cats shuttling in and out. Except for the clutter, that’s generally how he likes it. Peter Van Toorn is happy.

He is retired now, retired from teaching and retired from writing. He hasn’t really written anything since the stroke in 1982. I wasn’t there, but from what I have heard about how hard he was driving himself, I believe the stroke may have saved his life. It forced him to stop writing. He says he used to write poetry, now he lives it. Actually, he channels poetic energies into his conversation.

“Peter Van Toorn is the most vulgar and at the same time the most refined person I know,”

—Jamie Hawes, Spring 2000

Peter talks in the most graphic way possible all the time, about sex, excrement, and violence. At the same time, between expletives, Peter is the universal scholar, always leading the conversation into the subtleties of love, art, religion, jazz, mythology, philosophy, history, and poetry. For many, this apparent contradiction suggests an infirmity that I don’t buy. One of his closest friends and colleagues at the college once pulled me aside and cautioned me against spending too much time with Peter by saying, “He’s nuts, you know.” I didn’t believe him then and still don’t. These days, clever people see disease everywhere. I see Peter as eminently healthy.

Rather, I would say Peter is the most cultivated man I know. He lives his life fearlessly and encourages others to do the same. If personal cultivation is measured by the degree of a person’s compassion, kindness and tolerance, Peter is tops. Peter befriends all the people that polite society routinely rejects or ignores, but in all his co-mingling he does not become base, he does not lose himself. The proof is when there’s a panic Peter is cool.

Once he was invited to a party at a Penthouse apartment in downtown Montreal. The party, he discovered when he arrived, was populated by all the drug dealers, pimps and prostitutes that service the Montreal elite. The host was openly passing around huge plates of cocaine, marijuana and pills for guests to sample. Without prejudice, Pete joined with them in conversation and a drink, politely declining the plates that came his way.

During all this, with the music blaring, there came a hammering at the door and a voice shouting: Open up! Police! The police had come to report a complaint from the people in the next skyscraper, so loud was this party. Of course no one knew this at the time, so the guests quickly began hiding their guns under the couches and the drugs in the bathroom where they could be quickly flushed should the police want to come in.

Seeing the panic caused by the arrival of the police, Peter turned the music up (not down) and went to answer the door himself. With a martini in one hand and a cigarette in the other, he opened the door to talk to the officers. “Hey, glad you could make it,” he grinned. “What a party! We’ve got coke, booze, pot—you name it, man. This is the place to be. Get in here, guys, stay a while.” Well, that got the policemen laughing and they explained that they were sorry to disturb the party but there had been a complaint about the noise. And then they left. When Peter closed the door and went back upstairs, he returned to a hero’s welcome. I don’t know anybody else who could pull that off.

Peter has a shaman’s ability to knock you into new realms of detachment and contact with the world. Last winter while out walking his three dogs, he bent down to pick up after his largest dog, Dali (half shepherd, half great-Dane). Standing up with a rather full plastic shopping bag of dog shit, he presented it to me to hold. “Feel the warmth in that. That’s good shit, that.” Though stunned at having a bag of shit in my hand, I had to admit the bag was warming my cold hands. Now, everyone I tell that story to is horrified. They are astounded that anyone could be so barbaric as to handle a plastic bag of dog shit and evaluate it on the basis of its heat giving properties alone. If they are clever, they dismiss it as the indifference of a lunatic. “Pete’s finally gone over the edge,” they sigh. But Peter is in no way indifferent about the world. Peter is a poet deeply in touch with the raw physicality of life. Dog shit doesn’t scare him.

Peter examines, with great curiosity and detachment, things that normally cause ordinary people to turn away in horror and disgust. He finds beauty in garbage heaps. Consider these lines from “Shake’n’bake Ballad.”

…in long peels of oven grease

in wormpie and roachpaste

in cigarettesog of tavern urinals

in rats’ sewer water

in coffinslag and maggotmatting

in plasters of runover skunk

and in viler things

shake’n’bake their envy schooled tongues…”

Montreal poet Billy Neale calls Peter’s explosive images “megaphors.” Metaphors won’t do anymore, Billy reasons. These days you have to knock people over the head to get their attention. That’s why Peter writes that way. He wants to provoke a response in a populace totally hypnotized by TV. Remember this is a man who, over the course of 57 years, has turned over libraries in his attempt to educate himself.

Peter Maria Van Toorn was born in Shraveningen, Holland on July 14th, 1944. His father was a self taught electrical engineer, the son of a police chief. This police chief, Peter’s grandfather, was totally illiterate all his life and relied on Peter’s school aged father to handle all official correspondence from his superiors. Though most of his grandfather’s life is “shrouded in mist,” he told me that he learned from his father that his grandfather wore a sabre on horseback as a young man in one century and wore a pistol and rode a motorcycle in the next. Nothing else is known about him except that by day he worked in the police, by night he built the house Peter’s father grew up in.

The only story Peter tells of his grandmother is about how once his father was invited to dinner at a lord’s manor in Holland and brought Peter’s grandmother along. She was a simple woman, so when they sat her at the banquet table with the confusing array of silverware laid out in front of her and the soup arrived, she grabbed the spoon she liked best and started eating. All the other dinner guests were shocked that she had chosen the wrong one and a silence fell over the room. The lord of the manor, Peter’s father’s employer, seeing her error picked up the same spoon and started eating his soup. Then one by one all the guests followed suit.

Peter’s mother had class. Mrs. Maria “Marijke” Wilhelmina Van Toorn (nee Dekker) was born in Haarlem and came from a family of landowners. Though her father was for many years the general sales manager for a large chocolate factory in Amsterdam, they were heerboer (farmer nobles) and were permitted to show an insignia of a swan on their barn to advertise the fact. Peter says she was a great talker and had the social graces her husband, “Cees” Cornelius Hendrikus Van Toorn, lacked. She loved her husband and tolerated his womanizing without complaint. She was, however, terrible with money and squandered everything after his death in 1976. She died in 1996.

Cees (pronounced “Case”) was a successful inventor. Among other things, he developed speakers for Phillips, modernized industrial calendars (rollers for finishing plastics and paper), and developed a diagonal breaking system for cars that became standard issue for Austin Motors. After a falling out with his employer, Lord Jankheer, he came to Montreal where he became a test inspector for Air Canada in 1952.

Peter was a child prodigy of sorts. His mother was in her mid-thirties when she had him. He was not, however, an only child; he has a younger brother, Charles, who Peter believes was the product of an affair with a Jewish friend of the family.

This is not known for certain, but conveniently explains the differences in temperament between the two brothers. Charlie never liked Case, Peter’s father. He found him an embarrassment, an offense to his middle-class notion of how fathers should be. Case it seems had stacks of X-rated magazines in his workshop, sang silly songs to himself and flirted shamelessly with Peter’s mother when she was cooking.

Peter says that after a dinner party at their house one-day, his mother asked Charlie if he had liked the dinner guest. Charlie said that he did and then his mother told him that the man who had just left was his biological father. Peter is not sure whether it was his mother’s misguided intention to give the boy a father figure he could admire in place of the father he loathed, or if she was telling the truth. Instead of being a relief to the child, the news devastated Charlie. Charlie became further alienated from Case and developed a greater sense of horror about his family. The normalcy he so desperately craved in a family was now completely out of reach for him.

Peter really admired his father. He tells the story of how as a child he visited a rich industrialist’s laboratory in Holland with his father who was looking for backing for an innovation he had made in ceramic heating coils for heating water. The industrialist’s engineers were very skeptical about his design. Using ceramic electrical heating elements immersed in water, though common place nowadays, to their thinking presented an unacceptably high risk of electrical shock.

While they were discussing this, the young Peter was playing a dangerous game outside. Peter had been observing the opening and closing of the immense iron-gate to the courtyard of the industrialist’s laboratories. He noted the regularity of the gate coming down each time a delivery truck arrived or left and decided to test his reflexes by placing his foot under the gate and at the last moment pulling it back before the gate could get his foot. Each time he got more and more daring, and each time at the last moment he pulled his foot back unscathed.

What he had not counted on is that mechanical devices fail at times. This time on its way down instead of gliding smoothly to the ground as it had before, the gate stopped briefly eight inches off the ground and then suddenly dropped the rest of the way onto little Peter’s foot.

With his foot caught under this monstrous gate, Peter let out a cry for his father. His father came running out, freed Peter’s foot and carried him inside the laboratory. There he took his son’s shoe and sock off to reveal the badly bruised foot. To the shock and amazement of the on-looking engineers, Case immersed Peter’s foot in the water inside his prototype water heater—with the electrical heating element switched on! Well, the engineers were so impressed by this demonstration of confidence in the safety of his invention that they contracted there and then to begin production of a commercial model. Or so the story goes.